The glass-and-steel atrium of Nairobi's Milimani Law Courts, where the hum of legal briefs and the shuffle of robed advocates blend into a symphony of justice deferred and delivered, bore witness to a seismic reversal on the crisp morning of November 12, 2025. In Courtroom 7, Justice Olga Sewe, her gaze steady over half-moon spectacles, delivered a 38-page judgment that dismantled a Sh1.1 billion arbitral windfall awarded to software developer David Wanjohi and his firm Popote Innovations Limited, nullifying the payout on the grounds that no binding contract underpinned the alleged intellectual property theft by telecommunications giant Safaricom. The ruling, a meticulous dissection of contractual intent and evidentiary weight, upheld Safaricom's petition to set aside the November 2024 arbitral decision by retired Justice Aaron Ringera, who had found the telco liable for appropriating Popote's concepts in developing the M-Pesa Super App and M-Pesa Business App. "There exists no executed agreement, no meeting of minds, no consideration exchanged—merely a draft proposal that never crystallized into obligation," Sewe intoned from the bench, her voice echoing off the chamber's wood-paneled walls as Wanjohi sat stone-faced in the public gallery, his laptop—a relic of the disputed code—clutched like a talisman. "To enforce an award premised on a fictitious contract would be to mock the sanctity of arbitration and the rule of law."

The saga, a high-stakes tango of innovation and infringement that has captivated Kenya's tech corridors since 2022, traces its origins to the fevered days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when digital wallets became lifelines for a nation under lockdown. Wanjohi, a 38-year-old self-taught coder from Nakuru's Lanet suburb whose journey from fixing village cyber cafes to pitching fintech solutions mirrored the hustler's ascent, first crossed paths with Safaricom in March 2021. Through Popote Innovations—a boutique software house he founded in 2019 to craft payment gateways for SMEs—Wanjohi responded to a Safaricom tender for "next-generation M-Pesa enhancements," submitting a 42-page proposal titled "M-Pesa Omni-Channel Super App: Integrating Merchant, Consumer, and Enterprise Ecosystems." The document, a visionary blueprint, envisioned a unified platform merging consumer payments, business till services, bulk disbursements, and AI-driven analytics—features that would later debut in Safaricom's 2023 M-Pesa Super App launch. "We poured 18 months of sleepless nights into that pitch—wireframes sketched on napkins at Java House, prototypes coded in my bedroom while my wife rocked our newborn," Wanjohi recounted in his arbitral testimony, his voice cracking with the raw memory of opportunity's dawn. "Safaricom's team loved it—'game-changer,' they said in emails, promising partnership. Then, radio silence, followed by their app mirroring our DNA."

Popote's claim gained traction in June 2022 when Safaricom unveiled the M-Pesa Super App at a glitzy Michael Joseph Centre event, attended by 500 stakeholders and livestreamed to millions. The platform's interface—carousel menus for bill payments, QR-code merchant tills, and a business dashboard for bulk payouts—bore uncanny resemblance to Popote's mockups, down to the color-coded transaction flows. Wanjohi, watching from his Nakuru office, fired off a cease-and-desist letter through his then-lawyer, demanding Sh2 billion in royalties or 5 percent equity in the app. Safaricom's response, a terse email from its legal head, dismissed the allegations as "baseless speculation," citing independent development by its in-house team and Vodacom partners. Undeterred, Popote invoked an arbitration clause in a purported Memorandum of Understanding allegedly signed during a July 2021 meeting at Safaricom House. The document, a two-page draft initialed by a mid-level product manager, outlined "exploratory collaboration" but lacked signatures from authorized signatories, a fatal flaw Sewe would later seize upon.

The arbitral proceedings, convened under the Nairobi Centre for International Arbitration in January 2024, unfolded like a tech thriller over 12 hearings. Ringera, the retired judge known for his 2003 Goldenberg anti-graft crusades, heard Wanjohi's parade of evidence: email chains praising Popote's "innovative architecture," WhatsApp screenshots of feature requests matching the final app, and expert testimony from a JKUAT professor affirming 85 percent conceptual overlap. Safaricom countered with affidavits from its CTO and Vodacom engineers detailing a parallel development track initiated in 2020, predating Popote's pitch, and forensic audits showing no code plagiarism. Yet, Ringera sided with Popote in his November 2024 award, finding an "implied contract" through conduct and awarding Sh1.1 billion—Sh800 million for lost royalties, Sh300 million for reputational harm—reasoning that Safaricom's silence after enthusiastic feedback constituted acceptance. "The telco feasted on Popote's intellectual banquet without settling the bill," Ringera wrote, his 52-page decision a paean to David-versus-Goliath justice that sent Wanjohi celebrating with matoke feasts in Nakuru and Safaricom's shares dipping 3 percent on the NSE.

Safaricom's High Court petition, filed within the 90-day window under Section 35 of the Arbitration Act, 1995, was a surgical strike at the award's foundations. Represented by the formidable Hamilton Harrison & Mathews firm, the telco argued public policy violation: enforcing a non-executed draft would undermine contractual certainty. "This is not innovation protection; it is extortion by arbitration—a Sh1.1 billion lottery won on a unsigned scrap," Safaricom's lead counsel, Fred Ojiambo, submitted in oral arguments, his pointer jabbing at blown-up images of the MOU's blank signature lines. Wanjohi's team, now bolstered by LSK heavyweight Tom Ojienda, countered with equitable estoppel: Safaricom's reliance on Popote's ideas waived formalities. "They built an empire on our blueprint—justice demands payment, signature or not," Ojienda thundered, citing the 2018 English case of Reveille v Anotech where conduct implied contract. Sewe, unmoved, dissected the MOU's infirmities: no board approval, no consideration clause, no termination terms—mere "aspirational musings." "Arbitration is not alchemy; it cannot transmute a draft into gold," she ruled, setting aside the award and ordering Popote to pay Safaricom's Sh15 million legal costs.

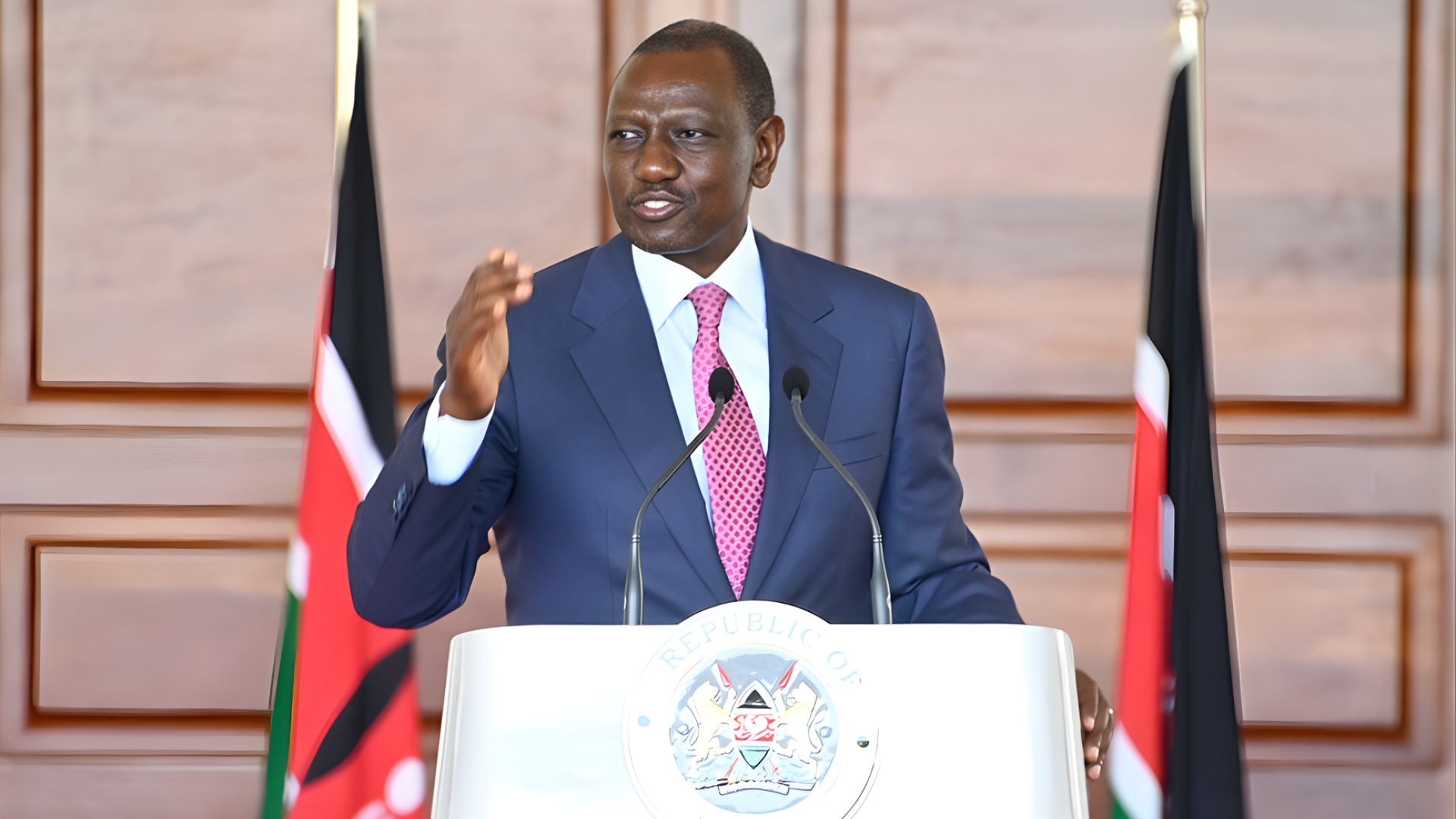

The judgment's ripples coursed through Kenya's tech ecosystem, a Sh500 billion sector where startups like Popote—bootstrapped on Sh5 million angel funding—vie with incumbents for digital oxygen. In Nairobi's iHub co-working spaces, where coders nurse flat whites and dreams of unicorn valuations, the ruling sparked heated Slack threads. "This chills innovation—pitch at your peril," lamented 29-year-old developer Mercy Njeri, whose fintech app was in Safaricom partnership talks. "No contract, no claim—harsh, but fair," countered a Konza Technopolis veteran, citing the 2023 Twiga Foods dispute where unsigned LOIs sank a Sh2 billion claim. Safaricom CEO Peter Ndegwa, addressing staff at a town hall on November 12, framed it as vindication: "We innovate in-house, with 2,000 engineers—Popote's ideas were generic, not proprietary. This protects genuine IP." Wanjohi, undeterred, vowed appeal to the Court of Appeal: "Justice Sewe saw a tree, missed the forest—our code's DNA is in their app. We'll fight to the Supreme Court if needed."

Popote's evidence, while compelling in overlap, foundered on provenance. The MOU, initialed by a product manager later sacked in Safaricom's 2022 restructuring, lacked the CEO's or board's imprimatur—fatal under the Companies Act's Section 34 on pre-incorporation contracts. Sewe cited the 2021 High Court precedent in Safaricom v Flashbay where unsigned NDAs voided claims. "Estoppel requires detriment; Popote's pitch was speculative, not commissioned," she wrote, dismissing Sh300 million in "reputational harm" as "self-inflicted by public grandstanding." Wanjohi, in a post-ruling presser at his Nakuru office—walls adorned with faded M-Pesa posters from his 2010 agent days—lamented the blow to SMEs: "Safaricom courts ideas, then crushes creators. Sh1.1 billion was our lifeline—now, bankruptcy beckons." His firm, employing 15 coders, faces Sh20 million in arbitral costs, with investors pulling out amid the reversal.

The M-Pesa Super App, now boasting 5 million monthly users and processing Sh1 trillion quarterly, stands as Safaricom's crown jewel—a 2023 launch that consolidated the wallet's 30 million users into a super-platform rivaling WeChat. Features like "M-Pesa for Business" tills and bulk payrolls, central to Popote's pitch, were independently developed, Safaricom insisted, with patents filed in 2020. "We engaged hundreds of vendors—Popote was one voice in the chorus," Ndegwa stated, announcing a Sh500 million innovation fund for vetted startups with ironclad contracts. The ruling, analysts predict, will tighten NDA protocols: "Pitch decks now need timestamps, NDAs, and board minutes," noted a Konza lawyer. For Wanjohi, the loss is existential: Popote's Sh50 million valuation plummets, staff layoffs loom. "From Nakuru cyber to national stage—now, back to square one," he sighed, his laptop screen flickering with the app's ghost code.

, a digital elegy for dreams deferred.

As November's rains pelt Milimani's corridors, the judgment endures as cautionary canon: in Kenya's digital gold rush, ideas are currency, but contracts are king. Sewe's gavel, falling like code compiled, compiles a lesson—innovate boldly, but bind tightly. For Safaricom, vindication; for Popote, validation denied. In the republic's restless runtime, where algorithms meet arbitration, Wanjohi's Sh1.1 billion mirage dissolves into mist—a Nakuru nightmare where super apps soar, but startups stumble without signatures.

The appeal, filed November 13 at the Court of Appeal, seeks stay of costs pending hearing. Ojienda eyes estoppel precedents from South Africa's 2022 fintech cases. Safaricom, in board minutes leaked to staff, celebrates "IP fortress." iHub coders draft "Contract First" manifestos. Wanjohi's wife, at home with their toddler, packs prototypes: "David's code lives—next pitch, with lawyers." In tech's turbulent tide, the ruling resonates: no contract, no claim—a binary truth in a nuanced nation.